How I'm Feeling Now

Brat was a cultural phenomenon—what was the point?

ARTICLES

ANDREW WOODWARD

2/3/202510 min read

I HATE K-POP SUPERSTAR J-HOPE

It was a relentlessly hot summer day in Chicago. Lollapalooza 2022 pulsed with life, and I was at its center, pressed between a sea of bodies surging toward the main stage. The air was thick with sweat, heat, and anticipation. My friend Sydney was down in the trenches with me, both of us swept up in the chaos. Our spirits were high despite the crush of people, however, because we were waiting to see the one, the only, the effortlessly iconic, Charli XCX.

There she was, one of my favorite artists, poised to perform at one of the biggest stages I could ever see her on. Yet, as Charli’s set approached I couldn’t help but notice something felt... off. She was moments from stepping on stage but the energy around us felt flat, almost totally deflated. The crowd, for all its size, seemed detached—people lounging on blankets, others idly playing cards, and far too many faces that looked completely uninterested. Where were the glittering twinks in mesh tank tops? The Twitter stans fervently live streaming? The bisexual girls and their straight boyfriends sniffing poppers?

That’s when it dawned on me. Charli’s set, while monumental to us, was right before a behemoth. What I failed to account for was the gravitational pull of the artist after her: J-Hope. J-Hope, formerly of BTS. J-Hope, making his American solo debut. The anticipation surrounding him was immense, and while I had little personal investment in anything related to K-pop, it was clear that his presence overshadowed Charli’s in ways I hadn’t imagined.

I needed to know for sure. In a surge of panic I blurted out to the crowd, "Who’s actually here for Charli?" My eyes scanned the faces around me and my heart sank as I saw one lone figure—a curly-haired white guy in his mid-twenties—sheepishly raise his hand, then wipe his glasses. Oh my god, we were surrounded.

The realization hit with a sharp pang of resentment. I had no animosity toward K-pop or its legions of fans, not in principle. But the feeling I carried in that moment, the quiet fury, has likely etched itself into me for good. I know it wasn’t his fault, I know he did nothing wrong, but I will probably hold at least a little hate in my heart for J-Hope forever.

MORE

BY ALICIA CAMILLERI

I love telling this story because it feels almost surreal to think about now. Imagine being in a crowd of people before a Charli XCX show and the energy not being entirely about her? Please. Just two summers after that performance at Lollapalooza, Charli released brat and skyrocketed into the stratosphere of superstardom, selling out arenas across the globe.

But let’s be clear: Charli wasn’t exactly an unknown before brat. For nearly a decade she had been crafting boundary-pushing pop anthems, earning immense respect within music circles long before her mega-breakout moment. Many fans trace the moment she came into herself as a pop pioneer back to the 2016 Vroom Vroom EP, a collaboration with the late SOPHIE that marked a turning point in her career (no shade to the Track 10 truthers—I’m just trying to keep it concise). Charli perfectly defined her pre-brat status in her own lyrics: “famous, but not quite.” She was a cult favorite, especially within queer communities, but hadn’t yet cracked the mainstream. Sure, she had massive hits like Fancy with Iggy Azalea, Boom Clap, and I Love It, but Charli XCX wasn’t a household name.

And honestly, I think she liked it that way. There’s something undeniably cool about being the “favorite reference” for so many talented artists, a secret revered by those in the know. But with her 2022 album Crash, Charli made a deliberate pivot toward mainstream success. The album was designed to be more accessible, less experimental—a calculated move to broaden her appeal. In interviews, she described Crash as a “performance art piece,” but one that could also be enjoyed simply as “a great pop album.”

Crash became Charli’s most commercially successful album to date. People loved it, I loved it. But even with its success, Crash came and went. She was more famous than ever, sure, but still… not quite. That moment—the one where she truly became undeniable—came two years later. And when it did, it was meteoric.

FAMOUS BUT NOT QUITE

To say that the release of brat and the cultural phenomenon it sparked was exciting for me, a longtime Charli fan, would be a massive understatement. Witnessing her music being so widely embraced, celebrated, and adopted beyond the insular, pretentious boundaries of “music appreciator” elitists was thrilling. And this wasn’t just any album—it was a wild, experimental project that, despite immediately following Crash, felt far more like a direct successor to her eccentric pandemic-era masterpiece, how i’m feeling now. Beneath the heavy autotune and densely layered production, there’s a raw authenticity that radiates from deep within every track, and it’s this honesty that so many people, myself included, connected with. There’s something uniquely surreal about being in a club throwing ass to lyrics like “Why I wanna buy a gun? Why I wanna shoot myself?” It’s absurd and darkly funny, but you’re never laughing at Charli—you’re laughing with her, caught up in the cathartic release of her unfiltered honesty.

That’s not to say authenticity is a new lesson I’ve learned from Charli’s music. She’s been in my ears for years soundtracking so many different points of discovering myself, particularly regarding my queerness. I have a vivid memory of one sweltering summer in college when I worked as a delivery driver, spending hours in my car with Charli on heavy rotation. I’ll never forget the moment I was stuck in traffic on an oppressively hot August afternoon, belting out Boys at the top of my lungs. After the fifth or sixth chorus of “I was busy thinking about boys, boys, boys, I was busy dreamin’ about boys, boys, boys,” I paused the song, caught my reflection in the rearview mirror, and quietly said “...Oh.” I’d known I was at least a little gay long before that moment, but I do look back on that now as a point of radical acceptance.

BRAT TIME

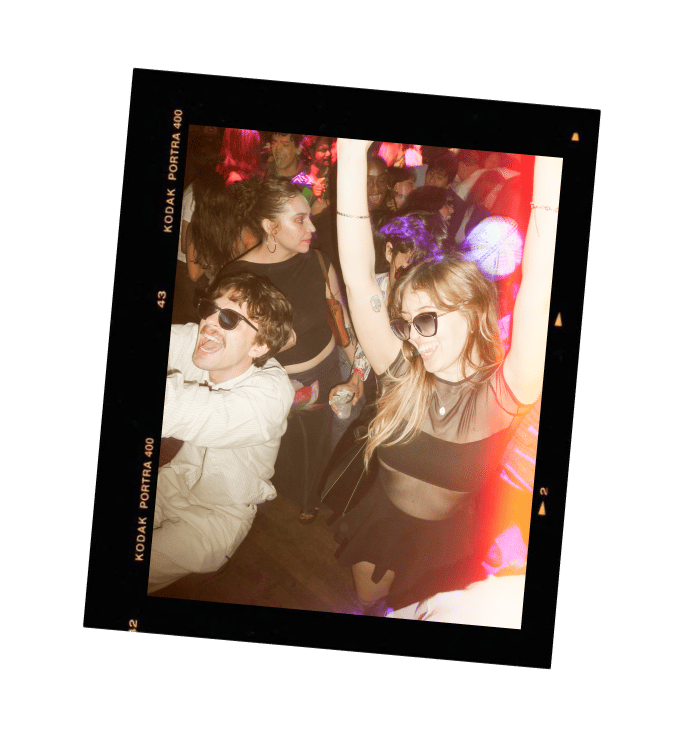

When brat dropped, I was all in from day one. I remember walking into the back room of Coconut Club on a sticky, humid night in June, just days after the album’s release. As soon as the opening synth hits of 360 blasted through the speakers, my friends and I screamed, twirling each other around in excitement. It was early in the night, and we were the only ones on the dance floor, but we couldn’t stop laughing at how happy we were to hear it at a club, especially so soon after it had come out. I went up to the booth and told the DJ we would take as much of that as they wanted to give us, and they obliged.

The release of brat also happened to align perfectly with the beginning of a new relationship—one that, to me, felt as seismic as the album itself. On our very first date we gushed about how excited we were for Charli’s new music and over the course of the summer we fell in love spinning and dancing to its songs. It became the soundtrack to those early days—a shared enthusiasm that brought us together.

From that first weekend, the brat snowball began rolling until it completely took over the club scene in Austin, or at least all the clubs I was going to. It felt like every Saturday night a different bar was hosting a brat-themed event, and my friends and I were punching our cards at every stop. The cultural embrace of brat and its ethos felt like it gave me permission to be able to go out and have fun without the usual anxiety that plagued me the morning after. Charli’s vulnerability in addressing intrusive thoughts or the complicated emotions we feel toward our friends made those common post-party stressors feel so much more manageable.

That whirlwind season of relentless energy couldn’t last forever, of course. It’s the end of January now; brat summer is long gone. The clubs are anemic and the bars are struggling to keep their doors open. The air is sharp and cold, and the wind bites at my hands when I’m out walking my dog. I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on this past summer, and I can’t help but wonder what I’m left with after such an intense, chaotic period in my life. What I got out of my “brat summer” beyond a broken heart and a functional cocaine addiction.

Looking back, I see the phenomenon as a coping mechanism—a way to escape the relentless terribleness that was 2024. The election, the natural disasters, a school shooting, another school shooting, some governor being a bastard somewhere, near-constant attacks on marginalized communities—a genocide. I needed an escape, and I found it. My guaranteed “get-out-of-your-head free” card, gladly accepted at any and all participating bars. As a person who doesn’t seem to do anything but overthink (to an incessant degree), the offer was impossible to resist.

Inside my head, there was a constant tug-of-war between overwhelm and apathy. In the sober light of morning, I’d roll out of bed, look at my phone, and that familiar pit in my chest—the one that showed up early in college—would resurface. I’d walk my dog, trying to drown out the noise with a stupid podcast or an album. Sometimes it worked, but nothing ever did the trick like taking a shot of something that would make my eyes water and hitting the dance floor.

I recently listened to brat cover to cover for the first time in months, and I’ve come to look at it as an album just as much about the morning after as it is about the night out. And right now, I feel like I’m living in that “morning after.” Dancing to Club Classics and 365 is probably the most fun I’ve ever had at a club, but these days, I find myself drawn to the emotional core of the record in songs like I might say something stupid, So I, and I think about it all the time. I could write this off as a mere symptom of seasonal affective disorder brought on by the fact that I haven’t seen the sun in six days, and while I’m sure that’s certainly not helping things, it would be a lie. It’s more than that. That pit in my chest is back and it’s not going anywhere anytime soon. Things are bleak right now, and it’s really hard to imagine they don’t only get worse.

THINKING ABOUT IT ALL THE TIME

I experienced a moment of deep hopelessness a few days ago. It was one of those lows where you have to pull out your phone because you know you really ought to talk to someone. As I scrolled through my contacts, I was struck by how many people I felt close enough to call. I’d been struggling immensely trying to make sense of the lowness I felt now coming off the high that was the summer, but looking at the names and silly contact photos of all those people I love so dearly made that moment of deep sadness become one of gratitude. It made me cry.

I thought my “brat summer” was just about partying. I thought I was going to write an essay about how buying so hard into aesthetics for their own sake was fun but ultimately hollow. I thought it would be about disillusionment. But writing this has made me realize that the authenticity at the heart of brat was also at the heart of my summer. Charli brought thousands of people together to celebrate that authenticity, and that spirit bled into every part of my life. In those few months, I made more friends than I had in years. I found community in such unexpected places, with people I never would have connected with at any other time in my life, and I am richer because of it.

There’s a pervasive feeling among young people right now that the world is ending, and if you find yourself in the throes of that headspace you know very well there’s not much you can do about it (except, like, go for a walk or something). But if my summer of moderate hedonism taught me one thing, it’s that you have to hold on to the people you love and that love you as tightly as you can. Find your community, or build it from the ground up. That way, when the world comes crashing down, at least you’ll have someone to dance with.