Nothing Matters Until It Does, and then It Doesn’t Matter Anymore

ARTICLES

Nathaniel Hendricks

6/27/20255 min read

I’m starting this review with a confession. When I started college in 2010, I was very nervous about making new friends. I spent the first couple days bumbling around campus and finding myself in clusters of classmates I had nothing in common with, trying to keep up conversations about stuff I didn’t care about. Determined to end this pattern, I spent a night going through a new student Facebook group and found every person who had Pavement under the “Music” section of their profiles (this is what Facebook was like when it was usable). In retrospect, this feels like an insane thing to do, but it worked. When I found myself in conversations with these people, I’d bring up Pavement, “the most important and influential band in the world,” as naturally as possible. At least one of these people remains one of my best friends.

When you’re young, friendships are established on secret handshakes and sacred knowledge. Pavement has always been one of those bands that can make a friendship between teenagers bloom. Pavement will likely always hold onto that sacred knowledge status. Even though they broke into the 1990s alternative-mainstream early on in their career, they somehow deflected the deathknell of selling out. They have always been a bug, not a feature, of the popular music machine.

According to Alex Ross Perry’s Pavements, that is precisely why the band is worth celebrating. That is why the band deserves a documentary, a concert film, a Hollywood biopic, a museum, and a Broadway musical revue. In keeping with Pavement’s ethos and legacy, of course, none of these things should be taken too seriously. Pavement deserves these things because they do not deserve these things.

The real Pavement

Pavement is one of the holiest of holy bands for a certain type of Gen X and Millennial, but the documentary would most likely feel unbearably inscrutable for someone who hasn’t at least taken Pavement 101. And even that isn’t necessarily enough. It also helps to be familiar with the documentary you’re watching. Pavements references itself in a flurry of news articles shown in the first ten minutes of the 128 minute runtime. The doc operates more successfully if you’ve been keeping up with its multifaceted, years-long production by having read, for example, the December 2022 New Yorker article “The World’s Most Important Musical About the World’s Most Important Band.” The article outlines the production of the fake/real broadway musical Slanted! Enchanted! In the film, Alex Ross Perry deadpans as the director who sits through A Chorus Line-style auditions and explains to hopeful actors who Pavement is while insisting it’s not a joke. Because it isn’t a joke. The fact that it isn’t a joke is crucial to the bit.

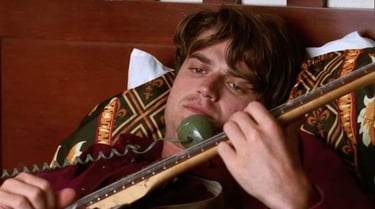

The musical is an experiment to see if Pavement’s irony can be transposed into Broadway sincerity. Meanwhile, the Hollywood biopic Range Life is pure ridicule. It stars Joe Keery as Stephen Malkmus, and its sequences have less to do with Pavement the band and much more to do with destroying the music biopic as a genre. Range Life plays in disjointed scenes taken from an Academy Awards screener, complete with a “For Your Consideration” watermark fading in and out. The scenes highlight not-quite-real turning points for the band, such as the release of the “what the hell do we do with this?” album that is Wowee Zowee. A scene between every band member and Matador record execs Chris Lombardi and Gerard Cosloy (Jason Schwartzman and Tim Heidecker, respectively) is intentionally edited like the infamous, much-shared table scene from Bohemian Rhapsody, a film which Alex Ross Perry and Joe Keery claim to be aspiring towards in a “behind the scenes” clip featured earlier in the documentary.

Joe Keery as Stephen Malkmus

Joe Keery has proven himself as the only good thing to come out of Stranger Things.

There’s a remarkable commitment to the bit of his intense method-approach to portraying the most laid back and laconic man in the world. He galumphs back and forth in front of projected concert footage, like Leonardo DiCaprio in The Aviator, mimicking Malkmus’ vocal cadence and physicality. I laughed really hard when Keery earnestly explains to his dialect coach why seeing a photo of Stephen Malkmus’ tongue would help him better inhabit the role.

Vibrating at a similarly ironic frequency to the biopic is the museum exhibition Pavements: 33-22, located in a Manhattan art gallery. The “artifacts” on display are not the only things that are inauthentic. So is the significance these artifact’s placards insist upon. The funniest display is the museum’s centerpiece: the original mud-stained clothes from Pavement’s infamous 1995 Lollapalooza concert. It doesn’t matter that the clothes aren’t the real deal. The point being made is that if the clothes were still around and stained with mud, they would deserve to be on display. It is perhaps more likely that the mud-stained clothes are from the dramatized version of the event as depicted in the biopic, which is intercut with archival footage.

And that sequence climaxes to Pavements’ best scene and most brilliant distillation of the entire point of this wacky exercise. After the Hollywood biopic version of Pavement dodge slung mud in front of a greenscreen Lollapalooza crowd, they sulk backstage in artistic frustration. By walking off, they have just blown one of the biggest opportunities of their career. But what’s the point if no one takes them seriously in the first place? Jason Schwartzman as Lombardi finds the dejected band and delivers a stern yet inspiring monologue. As the scene progresses, the Best Adapted Screenplay dialogue recedes to the back of the mix and is overtaken by a split-screen (comma, darlings on the) of “Actual Footage After the Mud Incident”. The entire band giddily laughs and bounces around the green room as they peel off their mud-covered clothes. They launch into bits and improvise silly songs. They are overjoyed that something so stupid just saved them from the misery of having to play at a music festival. The clumsy VHS footage steals all the attention from the gold-hued biopic.

In Pavements’ final stretch, Perry’s iron grip around the bit starts to slip. The last interminable half-hour focuses on why - surprise! - Pavement is actually important. The band members attend the opening of the Slanted! Enchanted! Musical. They participate in a Q&A at the premiere of Range Life. They reminisce at the “Pavements 33-22” museum. They diligently rehearse, then rock out in front of huge, sold out crowds. The film tells us why the reunion is so important, why the documentary you are currently watching matters, and why this is all so emotional for everyone - even sardonic and aloof Malkmus. If all of this is still part of the bit, well done. But please don’t tell me Pavement matters. If you do, I’ll stop caring.

But Pavements is not without its innovations and charms. I also got to hear Pavement songs for two hours. More films should experiment with established forms and rules, especially music biopics. That’s why I give Pavements three out of five Disco Balls.